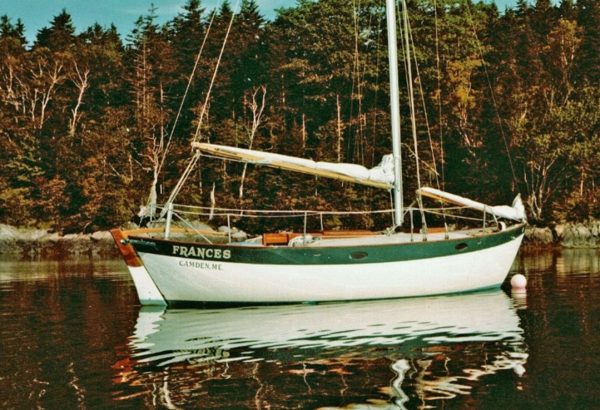

The very first Frances built by Tom Morris. It had a custom designed tall rig with double spreaders and added a genoa jib, so was an excellent performer. Tom Morris hit the ground running. The quality of every aspect of this yacht still is stunning, 47 years later.

The Frances 26 was my first successful design. I designed her in 1975. About 35 of them were built by Morris Yachts and 175 by Victoria Marine in the UK, and a few others built one-off in the WEST System all around the world. They are well-loved, built strong enough to last a century if well maintained, and highly sought after on the used boat market.

The Frances can be described as a heavy displacement double ender. Her hull is more vee shaped than many more recent designs, requiring heavy ballast for her stability and giving her a “big boat” feel. When originally designed she had a 50% ballast ratio, which makes her comparable to 12 meters, 6 meters, the Herreshoff 12 ½, and many of the early Sparkman and Stephens designs. These designs derive their stability more from a low centre of gravity, less from their hull shape. The rounded vee bottom is more easily driven than a boxier shape, so these yachts are unexpectedly fast for their hefty displacement.

TOM THUMB- custom built in Australia. If you were willing to carry a little too much sail she could even be raced, as she is here.

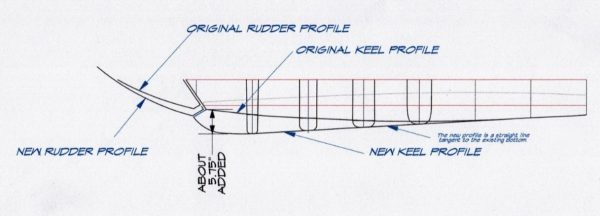

The Frances has a long, relatively shoal draft keel. The shoal draft is much admired, the continuous profile sheds lobsterpot lines and other flotsam, but her shoal draft limits her stability and pointing ability.

Her keel had an undulating profile that drew less than four feet. Its kicked up aft end might have been a mistake.

When first designed I drew two basic sailplans. One was a fractional rigged sloop with a tall mainsail and small, self-tending jib. The other had a three-foot shorter mast with a bowsprit and cutter foretriangle carrying a yankee and staysail.

The 7/8 fractional rig. It had a small self-tending jib and a quite tall mainsail. It was slow in light airs, as you see here. But once the tiny jib was replaced by a genoa, she became a great all-around performer.

With a genoa jib she performed really well in light airs and could carry on in heavier airs with a reef or two in the main.

The original British cutter rig. The Yankee and staysail are of the same size and height. With the addition of roller furling for the two small jibs it is still the best rig if one anticipates truly offshore sailing.

One of the original “British Cutter” rigged yachts. She could stand up to a lot more wind than the tall, racing oriented rigs.

The common cutter rig today. Often it was sailed like this, with just the Yankee. When the wind piped up you could just roll up the Yankee, hoist the staysail, and carry on with a tidier sailplan. Over the years the size of the Yankee was increased by owners and their sailmakers to this sail whose clew comes back about to the mast centerline. This perked up the light air performance at the expense of requiring reefing earlier.

The first two sailplans had modest sail area so they were compromised in light airs but could carry on in a pretty strong breeze before reefing. I would call the early boats mid-wind-range performers- faster than people expected in 5 to 20 knots of wind, but a little sluggish in light airs. When larger jibs were added to these two sailplans and the boomed jib abandoned, they became better all-around performers.

YANLI, shown in Bateman’s Bay, Australia. She has been sailed from England to New Zealand, thence to Hawaii, and back to Australia. Still looks pretty good after all those miles.

Quite a number of the yachts have done remarkably long passages, often singlehanded. YANLI voyaged from England to New Zealand, then to Hawaii and back to Australia. LA LUZ from Maine to Grenada and back, then to New Zealand. Numerous others have sailed transatlantic. It’s borderline foolhardy to cross oceans in such a small boat, but if you want to steer, trim, reef and anchor manually this design is one of the better choices. In fairness it must be remembered, though, that 26 feet is too small by far for prudent open ocean sailing as proven by the results of the 1979 Fastnet race, where the majority of abandonments and deaths occurred on yachts of less than 34 feet in length!

Over the years three things changed.

- Some owners saw the boat as too slow in light airs and asked for taller rigs so a few “racing rigs” with a 3-foot taller mast were designed. They heeled a lot more than the standard rigs, but made the boat truly quite fast in light airs.

One of the tall sloop rigs. It sails amazingly well in light airs, as shown here being sailed by its windvane self-steerer. Quite a few owners in the UK fitted the tall rig, with a larger overlap genoa run up for racing. But the maybe 110% overlap genoa shown here is a better choice for cruising- any larger genoas on the tall rigs caused the boat to heel too much.

This cutter rig is three feet taller than the standard cutter. The owner often sails it like this, without the outer jib. This looks to me very much like a “Folkboat” rig. Without a roller-furler, it is a bit of work to hoist and re-furl the outer jib, so it tends to be only used in light airs.

- With the advent of roller-furling and two-speed and self-tailing winches, genoas mostly replaced working jibs.

- Many convenience, comfort, and safety options were invented that found their way in stages aboard the boats.

Taking each point in turn;

- The Frances hull, even with its prodigious ballast, is too slack bilged to carry a tall mast of large sail area. Over the years I have learned that the shorter masted rigs, with about the same sail area but located lower down, are the best compromise between light and heavy airs.

- The replacement of a working jib with a genoa significantly increased the sail area of the jib, in a stroke solving the light airs problem. Thusly improved FRANCESes when compared with the Westsail 32, Southern Cross 31 and 28, and the Atkin Erics, were immediately recognized as much better sailing yachts.

Once the FRANCESes got genoas, they could really go in light airs, as LA LUZ illustrates here.

- Of the many new items that have been added to boats over the years, all weigh something, and almost all are well above the waterline. The one place where no weight has been added to most boats is the ballast. On many of the yachts 200 to 400 pounds have been added to the vessel’s topside weight with the addition of all these goodies. The Frances hull, though, is at its best with a 50% ballast to displacement ratio. The tall-rigged Franceses would benefit from the addition of 200 to 400 pounds of lead ballast as low as possible in the bilge. This would bring the stability and sail area back into equilibrium.

THE ”DANSKA” PROJECT

In an attempt to prove my theories of how to get the most out of a Frances, I am (was) restoring an old Morris hull and trying to do everything I can think of to maximize the sailing performance. I have torn it back to a bare hull with no deck, interior, or engine, so have complete flexibility to try anything. Listed below is what I am doing. Some of these ideas will be just too much work to be justified on a finished boat, but every one of these tasks would improve an existing Frances and I encourage folks to try one or two of them.

DANSKA on the day she arrived in Maine. She was Morris hull number 6. Her hull, ballast and mast were as good as the day she was born, but the rest was toast. She’ll be a great test platform for trying new ideas. If I live long enough to finish her she will be renamed FULL CIRCLE.

- When I designed the Frances I wanted reasonably shoal draft. I figured that in order to get as much stability from the lead ballast as possible the low point of the keel would be where the ballast ingot was, and I swept the profile upwards from there as it went aft. Over the years I have learned that I would have been better served to continue sloping the profile downwards to a deepest point just ahead of the rudder. I have added a robust grounding shoe/keel extender to the aft end of my keel. This adds two inches to the overall draft- six inches at the sternpost, will prevent the generation of a “wingtip vortex” when the yacht is hard pressed in heavy airs, and will enable the yacht to point closer into the wind.

- The rudder has been modified /deepened to match the new profile.

- The trailing edge of the rudder has been pared away to a narrower width than previously, and its profile deepened to match the deeper aft end of the keel. Fortunately DANSKA’s rudder was the last one made of marine plywood – it would be very difficult to make this change on one of the later fiberglass rudders.

- The heavy oak cheeks at the top of the rudder have been halved in size, to remove a bit of unnecessary weight at deck level

- I have added about 300 pounds of lead ballast as low in the bilge as possible. Thus even with all of the modern goodies, she will once again have a 50% ballast ratio.7DANSKA came with an aluminum, tapered mast for the tall fractional rig. It was a nice lightweight section. I plan to reconfigure the rigging to a single sweptback spreader with double lower shrouds. Otherwise it will remain as originally designed, with the addition of a genoa jib on a roller-furler.

- One thing I could have done, but haven’t, is to replace the aluminum mast with a carbon one. Mostly this is a matter of cost, plus the fact that I am an environmentalist and can’t bring myself to throw away a perfectly usable mast. I am working with another Frances restorer who has sprung for a carbon mast, and I am sure it will really sex up the performance of his boat

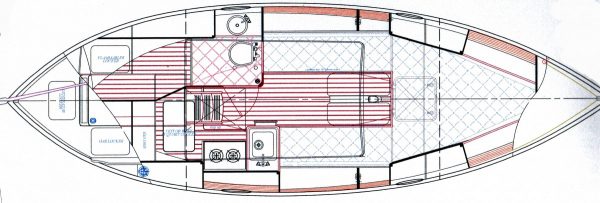

- DANSKA had the flush deck- no cabin house. And a simple, camping-style interior, with the toilet out in the open. I will replace this with a much more comfortable arrangement with the 5’ – 11” headroom house and an enclosed head.

We’ll see how it goes. I will periodically update my Facebook group, “Chuck Paine Yacht Designs Fan Club” as each improvement is added. Then when she is done I will put her through her paces using YouTube videos. I’m renaming her FULL CIRCLE.

My career began with a Frances, and will surely end with this one. I am sure I will end up loving her even more than my original Frances, which I built in 1976 and found to be an absolute joy.

My first FRANCES in 1976.