I’d like to introduce you to three new “classic” designs. They are all styled to look very much like a Herreshoff 12 ½ above the waterline, but are completely different below. I’ve owned a Herreshoff 12 ½ ever since I bought PETUNIA in 1972—an original Herreshoff Manufacturing Company woodie built in 1937. I loved and cared for her for 49 of her 84 years. All of my friends know that I consider the Herreshoff 12 ½ the finest small yacht in the world.

PETUNIA

Herreshoff 12 ½ profile

Herreshoff 12 ½ profile

The Herreshoff 12 ½ was designed by Nat Herreshoff in 1914. It was intended as an extremely safe small yacht, so stable and forgiving that it could be entrusted to one’s children, even on windy days. As such it is beamy and heavy, with a wineglass shaped midsection, and its hull and deck are lightly built so that the lead ballast ingot can be massive, comprising half of the weight of the entire boat. The way Nat engineered the top of the ballast casting with a curve to mate to the underside of the keelson rather than flat as on 99.9% of other designs—in order to maximize the ballast weight—was the stuff of genius. Its cockpit is huge, occupying two-thirds of the 15’-10” length overall. And Nat got the athwartship proportions of the cockpit absolutely perfect—the slant of the seats and the coaming, which serves as a backrest, and the distance apart of the inboard edges of the seats such that one can brace oneself against the opposite seat when the yacht is heeling. When yachts get bigger their occupants don’t, so no matter how much bigger a yacht might be, the cockpit has never been designed that is better than that of the Herreshoff 12 ½.

I closed my design office in 2008, thinking I had retired. But it wasn’t long before I got the urge to start designing and building boats again. So far I have designed three new sailboats and built two of them and found boatbuilders who want to build more. The three designs are shown here. It might be helpful if you look at the underbodies of the three and see if you notice the difference between them and the Herreshoff.

I closed my design office in 2008, thinking I had retired. But it wasn’t long before I got the urge to start designing and building boats again. So far I have designed three new sailboats and built two of them and found boatbuilders who want to build more. The three designs are shown here. It might be helpful if you look at the underbodies of the three and see if you notice the difference between them and the Herreshoff.

The story of these new boats began in 2005 when a client from Australia asked my old firm to design a 72 foot motoryacht, which he would build of aluminum in New Zealand. When the yacht was nearing completion he phoned me and asked me to help him find a sailboat to store on the boat deck. I started off by saying that the boat I’d seen most often as a sailing toy on yachts like his was a Laser. He responded that he was way too old for that—he wanted a heavily ballasted keelboat—something safe and non-athletic. I still remember his words. “I want something with real gravitas”, he said.

Look closely and you can see the burgundy hull of his 14-footer at the aft end of the boat deck. Its keel is stored further forward on the same deck.

That’s all I needed to hear. “The boat you want is a Herreshoff 12 ½”, I told him.

“I want one,” he said. I got to thinking—it couldn’t be a genuine HMC woodie—stuck up there in the tropical sun it wouldn’t last one season. Plank-on-frame boats are meant to be put in the water, swollen up until they stop leaking, and taken out at the end of the season. So I recommended he buy a Doughdish or a Cape Cod 12 ½, or have one custom built in cold molded wood. I had a niggling feeling something was wrong, though. “Give me a minute to look at your drawings,” I said. I came back to the phone and told him, “I’ve got bad news for you—A Herreshoff 12 ½ won’t fit.”

This shows REDWING being hoisted onto the boat deck by the yacht’s crane.

For a bit of fun I told him he had two options. One was to halt the construction of his 72-footer and have us get started designing a 100-footer so a 12 ½ would fit. He laughed at that and asked, “What are my other options?” “Well, we could design something like a 12 ½, but smaller.”

And that’s how the 14-footer got started. At first I thought we’d just scale down a 12 ½ and have him build it oneoff in glass or cold molded. But he threw us a curve ball. “I don’t want it sticking up there like a sore thumb”, he said. This guy was all about aesthetics. I looked at welding in some sort of bucket in the boat deck for the keel to drop into to lower everything, but there was no place to put it that didn’t hang down into the accommodation space below. So I came up with the idea of a removable keel. I couldn’t think of a way to engineer the removal of a full length keel like that on a 12 ½, and that led to the idea of a separate and shorter fin keel.

So he agreed on the design and had the boat built of cold molded wood in Auckland. He named it REDWING, and I know for a fact that he loves the boat. A couple of years ago he decided to put the big yacht on the market, but to keep the little sailboat until the day he dies.

This shows the similarities of the topsides, and large differences in the underbodies, of the H 12 ½ and my designs.

REDWING had a gaff rig. All subsequent owners have chosen Marconi.

In the water she looks like a Herreshoff 12 ½, being sailed by a giant.

THE PAINE 14

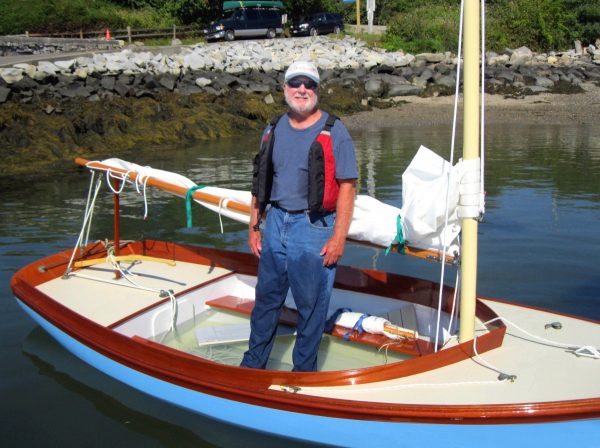

Flash forward a few years to 2012. I’d been retired for four years, wrote a book about my yacht designs and had traveled the world, and got the itch to build another boat. I had the design for REDWING and it was small enough to fit in my barn alongside PETUNIA in the winter. So I took a year and a half and built one for myself using the WEST system and named it AMELIA.

Me at age 69 doing what I love best—building a boat. There’s another name for boatbuilding–sanding!

I made a few changes. I chose a Marconi rig, because it was simpler to rig and offered slightly better performance, especially to windward. A carbon fiber mast made sense, meaning I could hoist it into place myself even though I’m in my 70s now and not very strong anymore, and it lowered the center of gravity, adding to the gravitas. I knew that it could be engineered to eliminate the need for stays, which has a real benefit in reducing windage.

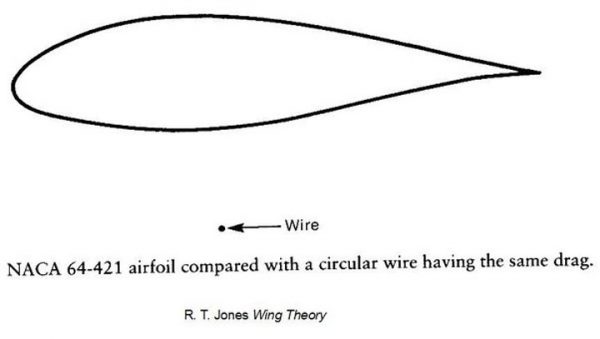

Why a freestanding rig goes to windward so much better than one with stays. The aerodynamic drag of the airfoil shaped wing and the tiny round stay shown here are the same, believe it or not! Eliminating a headstay, backstay and two sidestays is hugely beneficial going to windward.

I wanted the boat to be easily trailered. I had the idea that I might trailer the boat to some of Maine’s lakes and harbors that were too far away to sail to, or even to Florida some winter. The draft was only 2’-3”, so that was not an issue if I bought a trailer with a tongue-extender. And with its shallow draft and ability to short tack to windward thanks to the self-tending jib it would put the lie to the conventional wisdom that you had to give up sailing when you moved to Florida. This thing could be sailed inside most of those Florida canals even if the wind was blowing straight down the channel!

When you design a yacht for a client you cannot take risks at his expense. But since this boat

When you design a yacht for a client you cannot take risks at his expense. But since this boat  was for me, I had the opportunity to try out all sorts of ideas that had been rattling around in my brain for years. I had dreamed up a way of attaching a mainsail to the mast that was much easier and quicker than little slides and a track, using Velcro straps. Although it was the ease of rigging and unrigging that was my objective, I discovered when I sailed the boat that this had an unexpected benefit. The efficiency and drive of the mainsail was greatly enhanced—though it took me quite a long time to recognize why. I’ve written another web article just about this feature, and you can go to it by clicking here Velcro Straps.

was for me, I had the opportunity to try out all sorts of ideas that had been rattling around in my brain for years. I had dreamed up a way of attaching a mainsail to the mast that was much easier and quicker than little slides and a track, using Velcro straps. Although it was the ease of rigging and unrigging that was my objective, I discovered when I sailed the boat that this had an unexpected benefit. The efficiency and drive of the mainsail was greatly enhanced—though it took me quite a long time to recognize why. I’ve written another web article just about this feature, and you can go to it by clicking here Velcro Straps.

AMELIA– a PAINE 14 In this early photograph the roller-furling jib had not yet been fitted.

When I launched my new boat I got to experience the similarities and differences between it and my Herreshoff.

Being considerably smaller than PETUNIA and with less ballast—390 pounds of lead versus 725 on the Herreshoff—it had a smaller righting moment but I compensated for that by reducing the size of the sailplan proportionally (97 sq. feet versus 135 on the Herreshoff) and making the deadrise angle much flatter. The only thing that didn’t proportion linearly was the wetted surface—the wetted surface of the 14 was disproportionally smaller than that of the Herreshoff. Because of this, and being lighter overall—810 pounds versus 1450—it was more nimble and accelerated faster and in light to moderate airs just as fast or even faster despite its shorter waterline length. She was still stiffer than any other small boat I know of in the world excepting of course the prodigiously stable 12 ½, and I tried a few times to swamp her by carrying too much sail or failing to let the main out in a puff but I never could. She is, though, aimed at better light air performance than the H12, so she comes standard with a mainsail reef, unlike most Herreshoffs.

In case it ever did happen I wanted to know how she would float if swamped. If I ever swamped PETUNIA—and it would take an act of Congress to do so—I knew it would not end well. Only her forward area is watertight with no flotation aft, so she’d float with her bow sticking up out of the water and I’d have no alternative but to tread water nearby and hope to be rescued. But to be honest one wouldn’t last long in Maine’s cold water.

So I decided to test swamp AMELIA. I had some friends alongside to take photos and video. I tried standing on the side deck holding onto the mast and leaning out as far as I could, but she was way too stable to get close to swamping. Then I started rocking her hoping that might dip the coaming under a few times to let water in, but no dice. Finally I had to resort to bailing water in, and after a while she got low enough in the water for me to get one coaming underwater. She ended up floating dead level fore and aft, with remarkably little water in her once she was allowed to stand upright, and one could sit in her quite comfortably all day long if you wanted with no risk of hypothermia. AMELIA even had an automatic bilge pump powered by a high capacity battery, so you could just sit there if you liked and she would eventually bail herself dry! When I went on to design two similar but larger boats this auto-bailing capability found its way onto them—it was just too good an idea.

Fully swamped she floats level fore and aft and upright.

Click here to watch the video:

REDWING had a rudder that was completely unbalanced, similar to virtually every transom-hung rudder on other boats. Like all such rudders it had far too much “feel”…when weather helm develops in a breeze it pulls like a mother. I got to thinking, why not try to emulate a spade rudder? Spade rudders have some of the blade area forward of the pivot axis to relieve the helm forces. So I developed a rudder with some of its blade extending forward under the hull. The compromise on AMELIA was that in order to remove the rudder for maintenance one had to unscrew the gudgeons from the transom—you couldn’t just slide the rudder up out of its gudgeons because there was a hull in the way. Also meaning that if you snagged a lobsterpot line you had to work it off somehow, while removing the rudder would be a far easier fix. Later on I fitted all of these transom-hung rudders with a slide-rod connection that slid through gudgeons on both the rudder and the transom. You could just slide the rod out and the rudder would be disconnected from the hull.

Showing the “new” connection: Rudder, slide-rod and tiller.

This shows how part of the rudder extends forward of the pivot axis. Also shows the rescue step on the rudder. Not an easy thing to use but if it saved your life even once it”s probably worth fitting.

Then I got to thinking, what would happen if I fell overboard? Unlike any centerboarder she is far too stable to heel over toward you in the water and slither aboard. And at my age there is no way I have the strength to pull myself up over one side or the transom with nothing underwater to step on. So I came up with a rescue step shaped sort of like half a barracuda extending off of the trailing edge of the rudder. It’s beautifully faired so you never feel any turbulence on the tiller, and its top is flat so it wouldn’t be a bother if your feet were bare. You might get a bruised tummy using this thing, but you’d live to sail another day.

One day my fellow Yachting Magazine writer Dennis Caprio came up to spend a few days with me and do some sailing. We decided to take AMELIA out on a quite windy day. With Dennis at the tiller I cast off the mooring and a gust caught us just wrong and forced us to sail over the mooring pennant. Dennis happened to have the tiller all the way over to one side, causing a scissors-like gap to open up atop the balanced part of the rudder, and in she went! We had no choice but to lower the sails—not an easy thing to do being tethered stern to the wind. And to grunt and sweat and finally manage to push the pennant free using the paddle near the state of exhaustion. Then just to prove the point Dennis sailed over a lobsterpot line and we did the same thing all over again! I resolved to find some fix that would prevent this ever happening again.

What I came up with was a cone-shaped recess in the after part of the hull that the top of the rudder just fit into, sweeping the surface of that area with a paper-width of clearance. No way anything much thicker than a human hair could find its way into the virtually nonexistent gap.

The cove at the aft end of the hull.

Showing the tight clearance twixt rudder and hull.

At some point I took Todd French (French & Webb, INC, Belfast, Maine) sailing in the boat and he loved it. So he signed on as the licensed builder. We took AMELIA to three boat shows but the economy was still recovering from the 2008 crash and we made only one sale—my boat AMELIA. Unsurprisingly she was bought by the owner of a large motoryacht, to be lowered by crane from his boat deck for occasional sails just like REDWING.

AMELIA aboard her mothership.

The sale of the boat came as a shock. I still had PETUNIA, so I wasn’t boatless. But I couldn’t abandon the dream of trailering here and there, and I had absolutely loved the sporty performance of the smaller boat. So I set about designing a scaled-up version at 15 feet overall. Without the restriction of fitting into a pre-determined space I could design her at any size I liked, and 15 feet would be the right size to fit three people on the windward bench seat, but still small enough to fit into my barn in the winter. Todd French liked this size boat even better, and agreed to make a sizable investment in a mold and tooling to build them. He sold one right away to a guy who had sailed the 14-footer and agreed he liked the idea of a slightly larger boat.

THE LEVANT 15

Todd French changed the name of the design when he bought in. It had been called the Paine 15 and is now called the Levant 15.

Todd French changed the name of the design when he bought in. It had been called the Paine 15 and is now called the Levant 15.

The Levant 15 was a direct scale-up of the 14-footer. It sails just as beautifully—only a tad faster. And you can easily carry three people on the windward bench seat versus two on the smaller boat. Although all of these designs are heavily ballasted keelboats it still makes a big difference in heavy airs if you have weight to windward. After all, as all racers know, even on keelboats as large as a J-24, weight to windward really helps when there’s a lot of wind. The way this boat goes to windward in 15 to 20 knots of wind is joyful—if you have three bodies sitting to windward. It skips amazingly high into the wind and waves with you wondering how on earth the unstayed mast can possibly stay in the boat. But I’ve tried and I haven’t broken it yet. In this same amount of wind sailing singlehanded you’ll want a reef in the mainsail.

One thing I did was to fit roller-furling to the jib. This made it easy to get going and to put away the jib before coming into a mooring. This meant if there were any battens in the jib they had to be parallel to the luff so they didn’t prevent it rolling up. And this led to another invention.

The jib on all three of my latest designs is of very high aspect ratio. While this makes it more powerful and improves the pointing ability, high aspect ratio sails all have an inherent flaw… when you let “out” the jibsheet, the clew tends to go up, not out as you intended. And when this happens a lot of twist develops, with the top of the jib falling off and luffing, and the bottom of the jib overtrimmed and stalling. I dreamed up the idea of full-height battens extending all the way down to the foot of the sail. Their presence, combined with the bias strength of the sailcloth, prevents the foot of the sail from lifting. The effect upon the trim of the jib is remarkable—when you let out the sheet the jib goes out all of a oneness, eliminating the propensity to twist. You should be able to see this in the following photos and video. The battens also make it possible to roller-reef the jib without the “bagging” that happens if they are not fitted. One can roll the jib in to the forward-most batten and it sets beautifully, while reducing its area by about one-third.

The whole jib is working from top to bottom—there is just a little bit of twist, which is desirable.

The whole jib is working from top to bottom—there is just a little bit of twist, which is desirable.

It shows better here. The jib is let out on a broad reach with minimal twist.

I came to realize on AMELIA that I missed the presence of side shrouds to grab onto. The mast on all of these boats is freestanding carbon fiber and requires no stays. But when coming alongside in a dinghy or boarding the boat from a float I kept instinctively grabbing for the shrouds as one does, but they weren’t there! So I came up with the idea of leading the halyards out to the deck edge right where shrouds would normally be fitted, through little holes in the deck with turning blocks underneath, then to their cleats alongside the mast. The halyards had to exist anyway, so I wasn’t increasing the amount of parasitic drag, I was just moving it outboard where one could use the halyards for help in boarding.

It looks like the boat has shrouds, but no. Those are the halyards, led outboard to where they are easy to grab when boarding.

It looks like the boat has shrouds, but no. Those are the halyards, led outboard to where they are easy to grab when boarding.

The little holes in the deck that the halyards go through. The halyards then come inboard to their cleats.

The little holes in the deck that the halyards go through. The halyards then come inboard to their cleats.

When I built the 14-footer I fitted it with a mainsheet traveler, because I wanted it to look like a Herreshoff. What I forgot is the hundreds of times that the damned thing caused its traveling block to get hung up in a gybe and jam itself into the nice varnished inside face of the transom. I have come to hate travelers. So the Levant 15 uses the much simpler and snag-free approach shown below. There’s a block with a becket on one side of the afterdeck, and an opposing block on the other, and the mainsheet leads forward to a neat little camcleat built by Jim Reineck. The mainsheet runs nice and freely and there’s no possibility of it ever jamming.

The authentic traveler on the transom—its time has come, and gone.

The new configuration works much better.

For another video of her sailing click here: https://www.frenchwebb.com/levant

THE LEVANT 15 is much larger than a PAINE 14.

THE YORK 18

In 2013 an old boatbuilder friend, Mike York, asked me to design one of this new type of boat for him to produce in fiberglass. He had seen and liked the Paine 14 and said all the right things—mostly that he would build it to an absurdly high standard that would make me look good. The biggest difference was that his hull would be built of fiberglass, but he promised to put so much varnished trim on it that it would be just as lovely as Todd French’s boats—even a fully varnished transom inside and out.

ZEPHYRA, the first YORK 18.

The YORK 18 was a direct scale-up of the Paine 14. Like its predecessor it would have the freestanding carbon mast, vertical jib battens, high ballast ratio using outside lead ballast, Velcro straps, varnished Sitka Spruce boom and jibboom, roller-furling on the jib, automatic self-bailing, no-traveler mainsheet…the whole enchilada.

What had to be different? It was enough larger that I was concerned to keep the helm forces light, so I used a true spade rudder, which could have a higher proportion of balance area than the smaller boats. The varnished hardwood seats were long enough to accommodate four crewmen to windward if you were out to prove something in a blow, so they needed two support gussets to hold them up versus one. And the trailing edge of the rudder ended up further forward so the rescue step wouldn’t work.

She has a true spade rudder. Mike even tooled in the anti-snag little rudder cove I first used on the 14. The topsides are Awlgripped the color of the owner’s choice. This burgundy looked some nice!

I was determined to adhere to Nat Herreshoff’s magical proportions to keep the seating comfortable. If I had just scaled the cockpit width up linearly the distance between the seats would be too far apart for bracing when the boat heeled. This meant that the covering boards outside of the coamings had to be much broader than on the two smaller boats, requiring that they be gotten out of much wider planks, but this was merely a cost issue. The upside of this was that you’d choose the most beautiful boards in the stack for these, making the yacht a thing of exceptional beauty.

Mike knew about my obsession with falling overboard. It’s hard to see but look at the outside of the transom. There’s a little leather strap sticking out, and if you pull it a hinged door opens and out slides a shiny stainless steel, articulating boarding ladder that flops down into the water. When you’re finished using it you just slide it back into its watertight scabbard and close the door.

Mike knew about my obsession with falling overboard. It’s hard to see but look at the outside of the transom. There’s a little leather strap sticking out, and if you pull it a hinged door opens and out slides a shiny stainless steel, articulating boarding ladder that flops down into the water. When you’re finished using it you just slide it back into its watertight scabbard and close the door.

And does it sail as well as its younger sisters? Take a look at the following video and tell me what you think. It was only blowing about five knots when this clip was taken.

Click below:

Owner Barbara of ZEPHYRA takes Mike York for a sail.

Owner Barbara of ZEPHYRA takes Mike York for a sail.

A classy custom mast partners and leather mast cuff.

Lots of wind means lots of spray. But look at her go!

SUMMARY

The Paine 14, Levant 15 and York 18 are all beautiful, exquisitely well built, owner-maintainable, classic-styled sailboats of a size that can be trailered home to your garage for the winter. In designing them I wanted to honor Nat Herreshoff—the most skilled designer ever to fair a half-model—in emulating the look of his most universally loved design—the Herreshoff 12 ½.

My designs offer much higher performance, and with their maximum complement of crew on the windward seat (two for the Paine 14, three for the Levant 15 or four for the York 18) they can be driven to windward at excitingly high speed. When sailing with fewer crew or singlehanded, they all come equipped with reef points in the mainsail and all the necessary hardware on the boom, a reefable jib, and can even be sailed with the mainsail alone, another way of reducing sail in a blow.

My hope is that by designing these three yachts, and in reminding readers that the Herreshoff 12 ½ was a masterful design which even today is unequaled for sailing in windy locales, interest will shift from the ugly, price-driven consumer products that have passed for small yachts for the past fifty years, and our harbors will be embellished by these four beautiful, durable family-sized sailboats for decades to come.