I consider myself a disciple of Nat Herreshoff, whom boat nuts like myself practically worship. We’ve all heard the common query, What would Jesus do? I often contemplate the question, What would Nat do?

Captain Nat died in 1938—too early to experience the wonders of fiberglass and cold-molded wood construction, carbon fiber spars, synthetic, rot-proof sails or NACA foil research. But Nat employed new materials as soon as they emerged, with new hull shapes and sail plans to take advantage of them. Nat was the consummate engineer but he was an artist too, so throughout his long career he never drew a yacht, large or small, that wasn’t drop-dead gorgeous.

I spent my first few years on an island in the middle of Narragansett Bay in the state of Rhode Island. At the age of maybe five my mother would drive my twin brother Art and me around our island to ogle boats– our mutual passion. I pledged when I grew up I was going to be a yacht designer, like that legend named Nathanael G. Herreshoff from a few miles up the bay in Bristol.

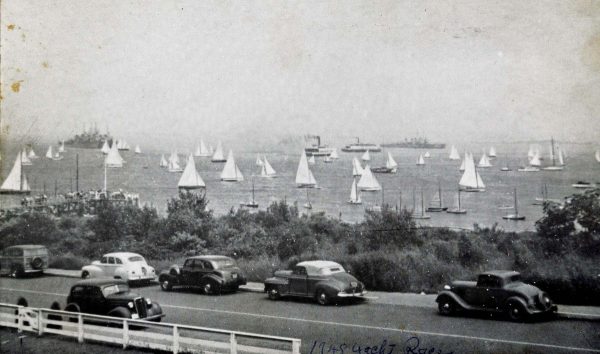

The view from Jamestown toward Newport in 1948. The two steam-powered ferries in the distance provided day-long entertainment for island kids at a cost of 15 cents. Virtually every yacht you see in the photo was designed and built by Herreshoff. Photo: Jamestown Historical Society

I had the drive and the luck to live my dream, and spent the major productive years of my life as a yacht designer, and retired having “launched a thousand ships”—or rather pleasure boats. Then, my yacht design business fell victim to the financial crash of 2008. But I couldn’t give up entirely. When customers for virtually everything under sail practically disappeared, Herreshoff fanatics like myself proved to be the last holdouts. So I decided to do exactly what my hero Nat would’ve done had he been able to live to a hundred and eighty. I asked myself, “What would Nat do today?” I applied 21st century science to a few of the most attainable (by virtue of being small) Herreshoff sailboats, and they’ve all exhibited minor improvement in terms of practicality and performance and enjoyed a spirited market. The look of them all is nearly indistinguishable from The Wizard of Bristol’s originals, on the theory that it’s impossible to improve upon the Master’s masterpieces.

THE HERRESHOFF 12 ½

Nat Herreshoff’s by far most popular design was the Herreshoff 12½. I’ve believed ever since I was a kid that the 12½ was the finest yacht design in the world. I bought one myself as soon as I became financially solvent, and have loved and cared for my Petunia for over 49 years.

The stability of this yacht is awesome, which is no surprise when you consider the class was designed for Buzzards Bay, where the afternoon sea breeze blows the feathers off the buzzards. There’s a lot of flare to the topsides. Narrow waterline beam and much wider beam at the deck stiffens the boat reassuringly as it heels. And like so many of Nat’s designs it has his famous “hollow bow.” I can’t say why or whether this makes the boat any faster, but it is one of the most beautiful bows in all of nautical creation. It’s true– they carry quite a bit of helm angle– but not helm force. The feel of the perfectly sculpted elliptical bulb on your tiller hand is light and lively as the fingertips of a dancer.

A 12½ is reasonably fast, achieving its hull speed of 4.7 knots in a decent breeze. I’ve had Petunia out in a 25 knot squall when going anything but dead downwind wasn’t going to end well, and the quarter wave climbed up the transom nearly to the level of the tiller hole. Somehow Captain Nat knew it would not rise any further, and it never has. A 12½ achieves a course made good about 90 degrees between tacks if you know what you’re doing, which is remarkable given that the lines consist mostly of a pretty wineglass shape with only a small proportion of what you’d term a keel.

The cockpit is probably the ultimate on any yacht regardless of size. The distance across from seat to seat for bracing, the angle of the seatback/coaming to support your back, the fact that you’re sitting with your butt close to the waterline so you hear the water sizzling past, all prove that bigger is not necessarily better. Because for comfort, just right is just right, and the 12½’s cockpit is– you guessed it– exquisitely right.

Petunia and your author. Jim Cleary photo.

For many years since 1914 the boat came only with a gaff rig. More recently though, most owners prefer the Marconi rig, which is simpler to rig and a little faster.

Petunia is 84 years old this summer. You can find and restore an original Herreshoff, as I did. Or Artisan Boat Shop in Rockport, Maine builds them in glued-seam plank on frame. Or you can get one in fiberglass from Ballentine’s Boatshop or Cape Cod Shipbuilding.

But what if Nat had designed these same yachts today? It’s fun to ponder what he might change. Here are my guesses:

- His hulls were built plank-on-frame, which means they can leak, and must be “swoll up” when launched every Spring. Today he’d have used seamless cold molded wood, or fiberglass.

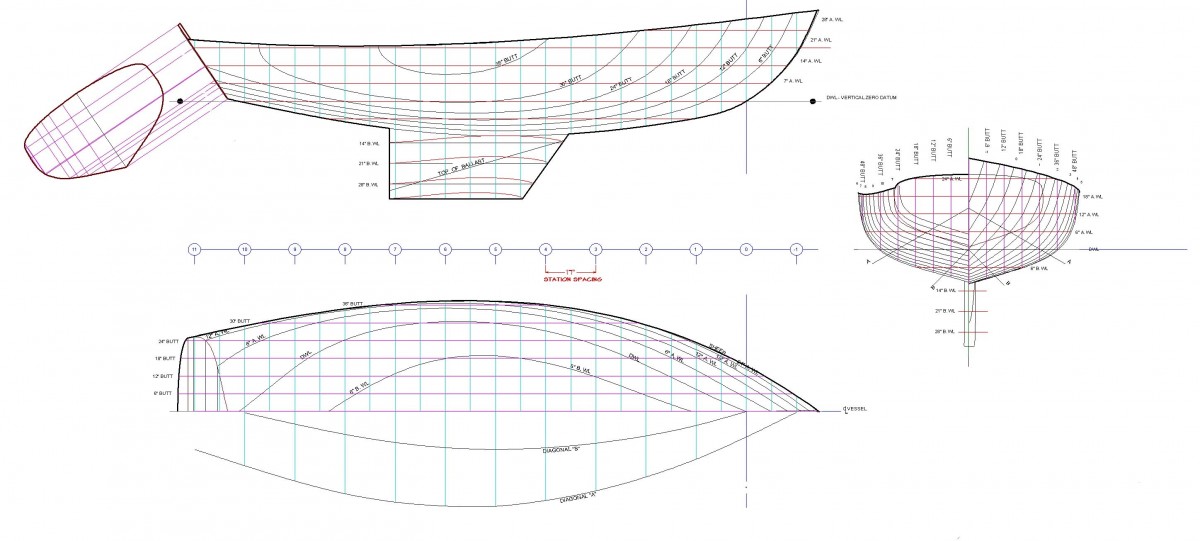

- The hull of a sailboat does one job, the keel quite another. I suspect Nat would today recognize this fact by flattening and lightening the hull proper, and fitting a fin keel– a third of the half models on his model room wall are configured as such.

- The lighter the mast, the lower the center of gravity. Nat would have specified a carbon fiber mast, which on this size boat require no stays. The lighter weight of carbon plus the absence of stays reduces the rig weight by half!

- He used good judgment and his intuition to design the keel sections. After he died, in 1949, millions of your tax dollars funded NACA research into the science of lifting surfaces– airplane wings and hydrofoils, keels and rudders. Nat would have studied this and used scientifically perfected foils.

- Nat was a racing yacht designer. Anything was permissible, as long as it made a yacht faster. He knew that as a yacht heels, the amount of the hull that engages the water gets longer– it “puts its ends to work”– so the more it heels, the faster it goes. Sailors nowadays think heeling beyond 30 degrees is way too much. So today he would have made all of his designs stiffer. Except the 12½, which is already perfect.

- Some of Nat’s designs had too much weather helm. Mathematical analyses and spreadsheets exist now that permit designers to tread ever closer to the hairy scary edge beyond which one dare not go.

- If it had been invented in his day, he’d have used roller furling on his jibs.

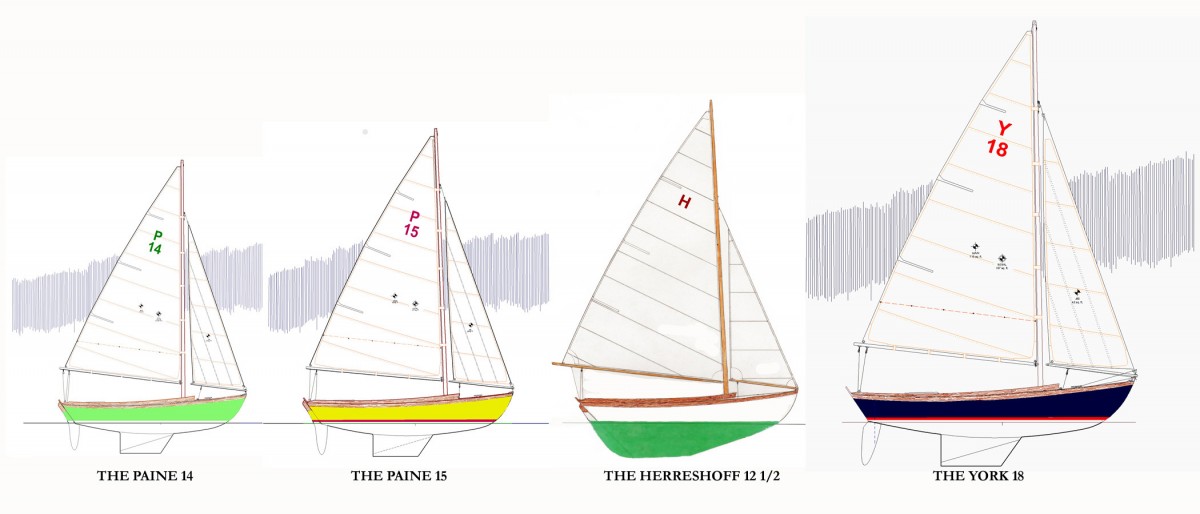

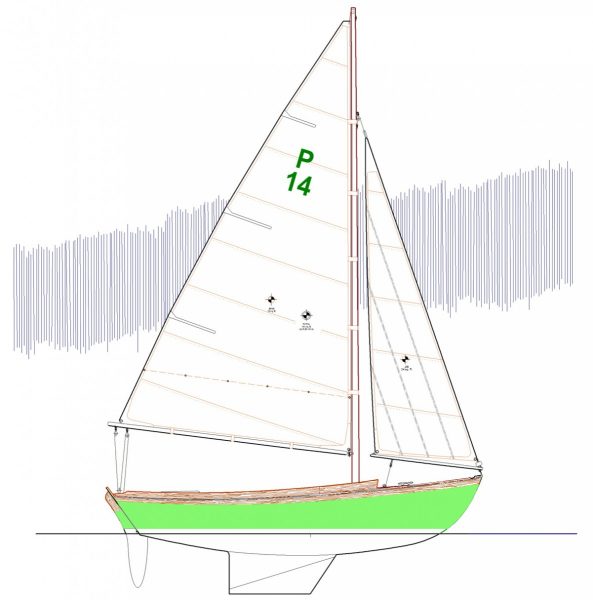

THE PAINE 14

The smallest answer to my leadoff question was designed in 2007 for an Australian customer to keep aboard the 72-foot aluminum motoryacht he was building in New Zealand. Since 14 feet of length is all that would fit aboard his boat deck, that became her length. He wanted her to look just like a 12½ in the water, with a heavily ballasted lead keel for safety, but to take advantage of every new material or technique that had emerged since the Herreshoff years. So she had flatter deadrise, a NACA foiled fin keel to reduce the wetted surface, a separate rudder, frameless epoxy cold-molded wood hull construction which reduced the weight, a carbon fiber mast which required no stays– eliminating a lot of drag to windward, and all the highly varnished trim and transom and sculpted wale strake details of an original Herreshoff 12½.

After I retired from full time work I built a sistership for myself, which I owned and tested for four years before selling her– Amelia now lives aboard an even larger motoryacht. This second yacht sought higher performance still so it had a Marconi rig, some partial balance to the rudder… the first such rudder ever to be hung on a transom to my knowledge, clever Velcroed “mast hoops” that make the mainsail much quicker to rig than conventional track and slides, and a roller-furler on the jib. The jib is on a boom so it is completely self-tending, as is of course the main. All of the yachts in this article may be fitted with either a gaff or Marconi rig. For consistency and so you can compare apples to apples, the Marconi rig is shown in all instances.

The biggest difference between the Paine 14 and the 12½ is that the newer boat is a true fin-keeler. No attempt is made to blend the hull into the keel. For all the beauty of this blended hull profile, which Nat used many times and Olin Stephens later perfected, it left the water wondering where the hull left off and the keel began. By separating the two, each can be designed to perform its separate task perfectly. The Paine 14 hull has much flatter deadrise, greatly increasing its form stability and reducing gobs of displacement. The entire keel sides are vertical, to more effectively capture low pressure on the windward side and high pressure on the leeward.

AMELIA, the second Paine 14, built in Chuck Paine’s barn. The yachts are now built by French & Webb in Belfast, ME.

Only 96 square feet of sail. But 45% less displacement and wetted surface than a 12½, so the SA/DISP and SA/WS ratios are higher.

She looks just like a 12 ½ with large people sailing her. Art Paine photo.

With watertight flotation compartments fore and aft of just the right size, if the boat is ever swamped she floats dead level fore and aft with something like 10 inches of freeboard to the coaming tops, and she even has a battery powered electric bailer which will bail her dry if you wait long enough. If I ever swamp Petunia, she’ll continue to float for awhile, but with her bow pointing straight up and my poor old body treading water in the frigid Gulf of Maine until one of us sinks.

Velcro straps replace tracks and slides. They’re lighter, much faster to rig and unrig, and even cheaper than a stainless track and slides.

Fully swamped, the Paine 14 floats dead level fore and aft, and she’s still plenty stable. I could have waited until she self-bailed but I wanted to go sailing again.

The partially balanced rudder with its integral rescue step.

Please God don’t strike me dead, but I know that she is faster on all points than an original 12½– I owned one of each for four years and occasionally sailed Petunia against Amelia with my equally skilled identical twin on the other’s helm. Being over 40% lighter, the acceleration of the smaller boat is quite remarkable, taking perhaps a boat length to regain speed after a tack. In light to moderate winds she’ll overtake the 12½ on any point of sail. At least, that is, until it’s blowing twenty knots or more when the brutal stability of a 12½ comes into its own and she’ll leave her little sister behind!

THE LEVANT 15

Two years ago I decided to design a slightly larger boat. Having owned Amelia for a few years, I got to thinking– how could it possibly be improved? It sailed amazingly well, so performance was not an issue, nor looks, nor safety. But to be honest, it was a wee bit small. Had to be– to be snatched by hydraulic crane aboard those motherships. The size of the 14 was no bother when you were actually sailing, and three people could easily fit– two on the windward side and a third sitting to leeward.

It was when hoisting the mainsail and unfurling the jib when she felt a bit cramped, though. You were on your knees facing forward at the front of the cockpit, and the space between the front of the seat at thigh level and the boom in its crutch at your shoulder, was just a tiny bit too tight. I figured if I scaled her up to 15 feet overall the ergonomics of the lengthened and widened cockpit could be almost exactly identical to the 12½, and you could easily fit a fourth and even fifth crewperson. It would still be considerably lighter than a 12½ with far less wetted surface, thus faster in most conditions. I found a boatbuilder who wanted to build them, right here in Maine. And importantly to me she would not compete head-to-head with the nearly 16-foot original 12½, Ballentine’s Doughdish, and Cape Cod Shipbuilding H-12, all of which deserve to be built forever. She would simply expand the availability of larger and smaller interpretations of the Herreshoff genre.

TODD FRENCH is my preferred builder of the beautiful, high performance keel sailboat, the LEVANT 15.

Todd French believes that elaborations upon the Herreshoff legacy in hand-crafted wood and epoxy represent the future of weekend sailing for urban sailors of means. He has convinced me that by investing in a vacuum-baggable closed mold, he can produce the yachts to a very high standard which will be indistinguishable from the original 12½, without those pesky seams.

THE YORK 18

So, what would Nat do at 18 feet overall length? Michael York of York Custom Yachts in Rockland, Maine saw all the fun I was having in Amelia, took a sail and verified its performance, and wanted to offer a similar yacht halfway in size between the H-12 and the larger Pisces. He commissioned the design of the York 18, and assured me it would be built and trimmed at a supremely high standard, using highly varnished teak trim. Of course architects of all stripes love to hear talk like this, because nothing makes a designer look better than a great builder.

All my new designs will feature the newly invented PAINE DVT jib vanging devices and a roller-furling jib.

The same hull shape as her smaller siblings, scaled up to 18 feet.

The hull shape is the now tried and true, scaled up proportionally. The one obvious difference is the rudder– the helm forces are significantly greater than the 14 and 15, or a 12½, so a more neutrally balanced spade rudder is fitted. Once again a boomed jib is used, so one can short-tack this yacht up a narrow channel and never touch either of the sheets as would be required with a genoa jib. Unlike all of the other yachts in these pages, her hull is of fiberglass– but with a varnished teak transom and Herreshoff-style sculpted top strakes just as Nat would have done.

CONCLUSION

I hope you have enjoyed this tour of the famous Herreshoff 12½ and my recent derivatives. Though Cap’n Nat acquired much of his well-deserved fame by designing some of the largest sailing yachts ever built, I believe he has brought the greatest joy to the world of sailing with this– one of his smallest. The fact that it has been imitated numerous times by myself and others (Joel White and John Brooks among them, whose excellent centerboard interpretations are so well known as to not need reprinting here), demonstrates just how brilliant the design was. Imitation is surely the sincerest form of flattery.

I believe we are at the start of a renaissance in the appreciation of the joy of sailing a well-designed and beautifully built new yacht. The ten-year depression we are finally emerging from sent many would-be boat owners chasing after old fiberglass boats depreciated to their scrap value. But there is really no pleasure to be derived from sailing scrap, and even less in spending the huge sums it inevitably costs to make these craigslist castoffs merely usable. It is my fervent hope that a decade hence the harbors and yacht clubs of our coastlines will spring forth with whole fleets of the lovely creations depicted here. I can just see old Nat cracking a smile in his grave every time you take yours out on the bay.

For those who own or have owned a Chuck Paine design, and those who aspire to owning one someday, here is a fun Facebook Group where you can meet and greet others with similar interests.

I have (with some help) created a Facebook group where people who like the boats I’ve designed over the years can meet and discuss. Take a look and consider joining and/or sharing with your boating friends. Just click the blue t3ext and join. https://www.facebook.com/groups/424532172574012/ “

I’ll be in the background serving as “moderator”. I’m hoping that many of the well- over- 1000 owners of a Paine design will enjoy belonging to this group.

Chuck Paine